Alchemy of Disappearance

2024

work in progress

Digital photo print of site-specific installation of traditional Hunza caps in Bisti Badlands, New Mexico, 34” x 48”

Alchemy of Disappearance

(Unearthing Stories From The Core series)

Alchemy of Disappearance (part of Unearthing Stories from the Core series) is a multi-sensory mixed media installation that highlights environmental devastation as a form of colonial violence while excavating histories and memories embedded in the land that connect us as people across cultures, time, and place. Alchemy builds on the eco-therapeutic practices of my past and ongoing work. Literally and figuratively, Alchemy of Disappearance draws together the lands of rural Pakistan and the US—seemingly disparate, ecologically fragile regions. This unexpected alignment reveals both geographic majesty and immense trauma absorbed by unceded land and its inhabitants.

Alchemy of Disappearance disrupts predominant notions of landscape in fiercely contested territories: Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Gilgit-Baltistan in Northern Pakistan. Site-responsive installations including Hunza caps from the contested region of Gilgit-Baltistan stand-in for displaced communities, such as Attabad, suffering some of the worst results of climate change. Mobile where human bodies are sanctioned, the caps speak to loss, to global connection, to the alchemy of hope.

The earth offers both a source of conflict and potential for healing. We are intermeshed with the subterranean realities on which we stand. The history of soil layers is that of micro- and macro histories. Of immigrants, of people displaced, of settler colonizers, of outsiders and refuge-seekers, and of of atomic violence and colonization in New Mexico.

Fusing otherworldly digital images with rich, elemental mixed media installations, Alchemy of Disappearance looks at land(scape) as a repository concealing and preserving our history. It is physical, cultural, ethnographic, historical, vernacular. Alchemy of Disappearance insists on a visceral understanding of ‘local’ environmental catastrophe as part of lager patterns, putting them into dialog as a call for policy change. It continually asks: how we might relate to land outside colonial, capitalist modes of living—a future of belonging, outside territorial possession or extraction. Living in mutual care. Incorporating elements of the local community from each location, it creates a trans-national exchange between populations at the margin, grappling with the meaning of “sovereignty.”

Digital photo print of site-specific installation of traditional Hunza caps in Valles Caldera, New Mexico, 34” x 48”

Digital photo print of site-specific installation of traditional Hunza caps in Bisti Badlands, New Mexico

Constellations of Disappearance

Bison at Sulphur Springs, New Mexico

Sarah Ahmad & Raúl Riquelme Hernández

Photography by Sarah Ahmad

Bison Fun Facts by Raúl Riquelme Hernández

(work in progress)

Bison are small stars lost in the American galactic landscape.

Digital photos of ephemeral installation: plastic bison at Sulphur Springs, New Mexico (Film, performance, and mixed media installations forthcoming.)

Raúl Riquelme Hernández is a Chilean playwright and performer. He has been active since 2016 writing for stage and audiovisual media. He also works in the Complejo Conejo collective and founded the Teatro Catástrofe theater company. SFAI Alumni for the SOVEREIGNTY residency.

Sulphur Springs, New Mexico

FUN FACTS - BY RAÚL RIQUELME HERNÁNDEZ

1. Bison are fascinating creatures. They are the symbol of strength and resilience of the United States of America. Some live in Colorado. Others in Oklahoma. Others in Utah. Others in California. But there are very few in New Mexico. So some must be ordered from Amazon. They are brought from China.

2. Thanks to Obama, who enacted a Bison Law, the bison population nationwide now reaches half a million. That's why most bison vote blue. Although they do it more out of commitment than values. Some believe that (REDACTED) the rest of the population. Those are the consequences of wanting to keep the bison race as pure as possible.

3. It is possible to locate the bison wherever you prefer.

4. Besides being the largest mammal on the entire American continent, bison are also one of the most important symbols of the United States. It's on the seal of the United States Department of the Interior, on the arrowhead logo of the National Park Service, and in the hair wax I keep in the bathroom cabinet.

5. As the main resource for Native Americans, good and white men decided to do what every good and white man would do: chase them until they nearly disappeared.

6. So we, being good but not white, have decided to bring them back where they belong. Some get a little lost in the landscape and bump into each other, but it's a matter of time for them to learn. They are intelligent creatures.

7. Bison are small stars lost in the American galactic landscape. Thousand-kilo stars that can live up to twenty years and eat twice their weight per day. They live in small groups, so they form small constellations, but no less important. Forgotten for many years by those who do not enjoy remembering, their numbers were reduced but they never stopped being there, jumping from head to head, wandering like ghosts amonglandscapes gnawed by the teeth of the nineteenth century.

8. For those who have never seen a bison in real life, I invite you to imagine one: imagine a gigantic mass of muscle full of brown fur, with a giant head -also fluffy, kind of cute in a way- and two protruding horns -horns that no one in their right mind would approach-. If you still don't understand, but you know cows, it's like a cow pumped up on steroids. I invite each of the readers of this text to crouch down, lie on the floor on all fours, imagine they have horns, and close their eyes. Then, give space your best roar. Now.

9. If you've never seen a bison, go to your nearest supermarket and ask for bison meat. Surely, somewhere, perhaps on a little sign above a generous mound of ground meat, there will be a drawing of a bison. They're also called American buffalo.

10. Sometimes I wish to believe that bison are the reincarnation of thousands of displaced souls in a distant past. That they think, feel, and reflect on how they were treated. And maybe they plan their revenge. How they ended up in a supermarket. How they ended up on the cover of hair wax. How their heads ended up adorning the living rooms of white mansions, neighbors of some elk or deer with a petrified gaze. I would like to know what they think of casinos, highways, real estate industry, water shortage. I would like to have a machine that translates animals so I can understand them and maybe share an ideology that only they know so far. But since I can't do that, I write speculations. And the bison, they roar. It's a sound that, to my ears, is a mix between a cow and a tiger. A very angry animal.

FUN FACTS - BY RAÚL RIQUELME HERNÁNDEZ

1. Los bisontes son criaturas fascinantes. Son el símbolo de la libertad de los Estados Unidos de América. Algunos viven en Colorado. Otros en Oklahoma. Otros en Utah. Otros en California. Pero hay muy pocos en Nuevo México. Así que algunos hay que pedirlos por Amazon. Los traen de China.

2. Gracias a Obama, quien promulgó una Ley de los Bisontes, la población de bisontes a nivel nacional hoyalcanza el medio millón. Por eso la mayoría de los bisontes votan azul. Aunque lo hacen más porcompromiso que por valores. Algunos creen que (REDACTED) al resto de la población. Esas son las consecuencias de querer mantener la raza de bisontes lo más pura posible.

3. Es posible ubicar a los bisontes en el lugar que prefieras.

4. Los bisontes, además de ser el mamífero más grande en todo el continente americano, también son unode los símbolos más importantes de los Estados Unidos. Está en el sello del Departamento de Interior de los Estados Unidos, en el logo de punta de flecha del Servicio de Parques Nacionales, y en la cera para el pelo que tengo guardada en el mueble del baño.

5. Al ser la principal fuente de recursos de los indígenas americanos, los hombres blancos y buenosdecidieron hacer lo que todo hombre blanco y bueno haría: perseguirlos hasta casi hacerlos desaparecer.

6. Así que nosotros, como somos buenos pero no somos blancos, hemos decidido traerlos de vuelta a donde pertenecen. Algunos se pierden un poco en el paisaje y chocan entre sí, pero es cuestión de tiempo para que aprendan. Son criaturas inteligentes.

7. Los bisontes son pequeñas estrellas perdidas en el paisaje galáctico americano. Estrellas de mil kilos que pueden vivir hasta veinte años y comer dos veces su peso por día. Viven en grupos pequeños, así que forman constelaciones pequeñas, pero no por eso menos importantes. Olvidados por muchos años porquienes no disfrutan recordando, se redujo su número pero nunca dejaron de estar ahí, saltando de cabeza en cabeza, paseándose como fantasmas entre paisajes roídos por los dientes del siglo XIX.

8. Para quienes nunca han visto un bisonte en la vida real, les invito a imaginarse uno: imagínense una masa gigantesca de músculo llena de pelo color café, con una cabeza gigante -afelpada también- y dos cuernos sobresalientes -cuernos a los que nadie en su sano juicio se le ocurriría acercarse-. Si todavía no lo entiendes, pero conoces a las vacas, es como una vaca hinchada en esteroides. Invito a cada uno de loslectores de este texto a agacharse, tirarse al piso en cuatro apoyos, imaginar que tienen cuernos y cerrar los ojos. Después, regálale al espacio su mejor bramido. Ahora.

9. Si nunca has visto un bisonte anda a tu supermercado más cercano y pide carne de bisonte.Seguramente, en alguna parte, quizás en algún cartelito encima de un generoso montón de carne molida, habrá un dibujo de un bisonte. También le dicen búfalo americano.

10. A veces me gustaría creer que los bisontes son la reencarnación de miles de almas desplazadas en un pasado remoto. Que piensan, sienten y reflexionan sobre la forma en que fueron tratados. Y a lo mejor planean su venganza. Cómo terminaron en un supermercado. Cómo terminaron en la cubierta de una cera para el pelo. Cómo sus cabezas terminaron adornando los living rooms de las mansiones blancas, vecinos de algún elk o un deer con la mirada petrificada. Me gustaría saber qué piensan de los casinos, de las carreteras, de la industria inmobiliaria, de la falta de agua. Me gustaría tener una máquina que traduzca a los animales para poder entenderles y, a lo mejor, compartir una ideología que hasta ahora solo ellosconocen. Pero como no puedo hacerlo, escribo elucubraciones. Y los bisontes, braman. Es un sonido que, a mis orejas, es una mezcla entre vaca y tigre. Un animal muy enojado.

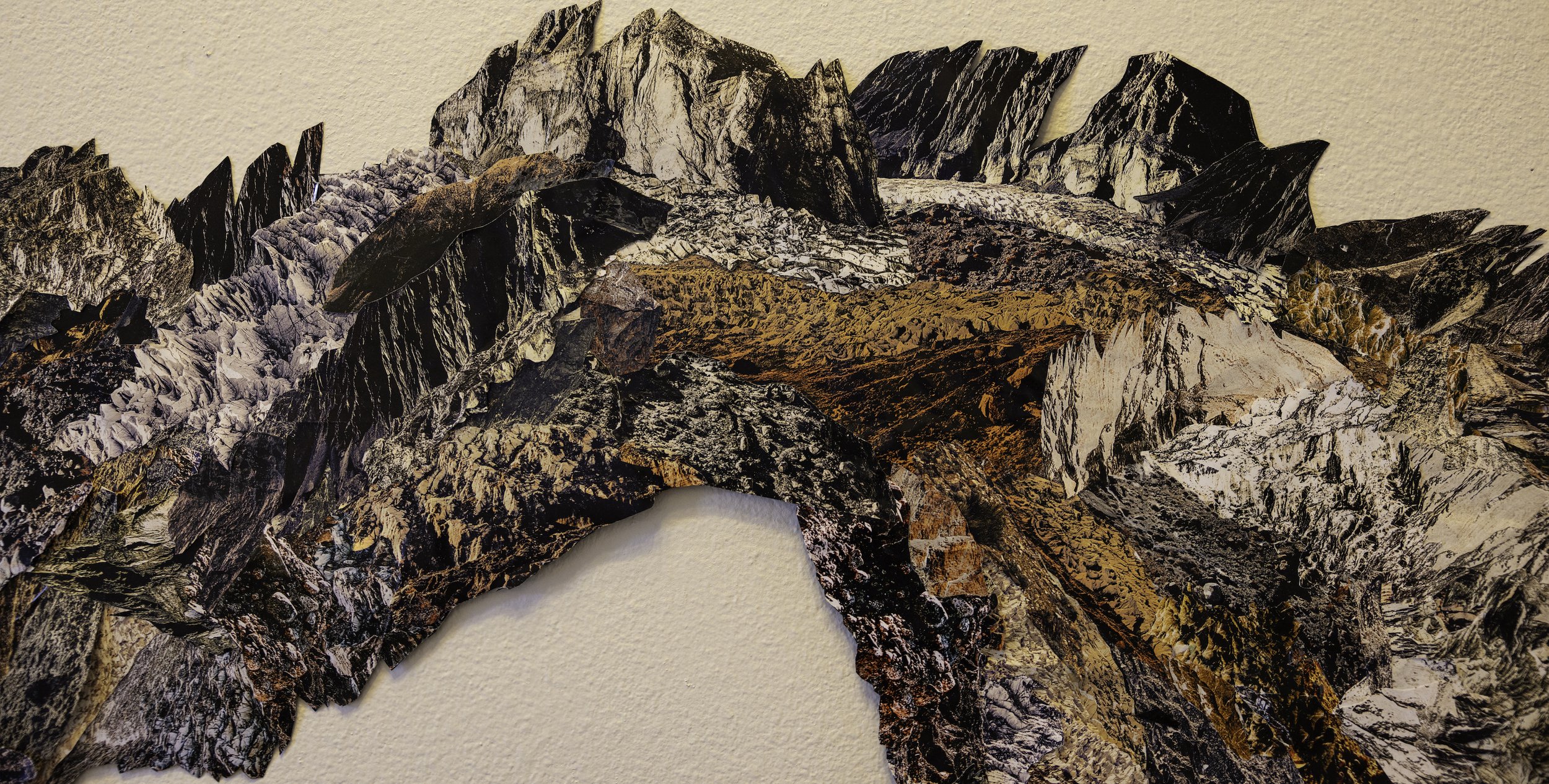

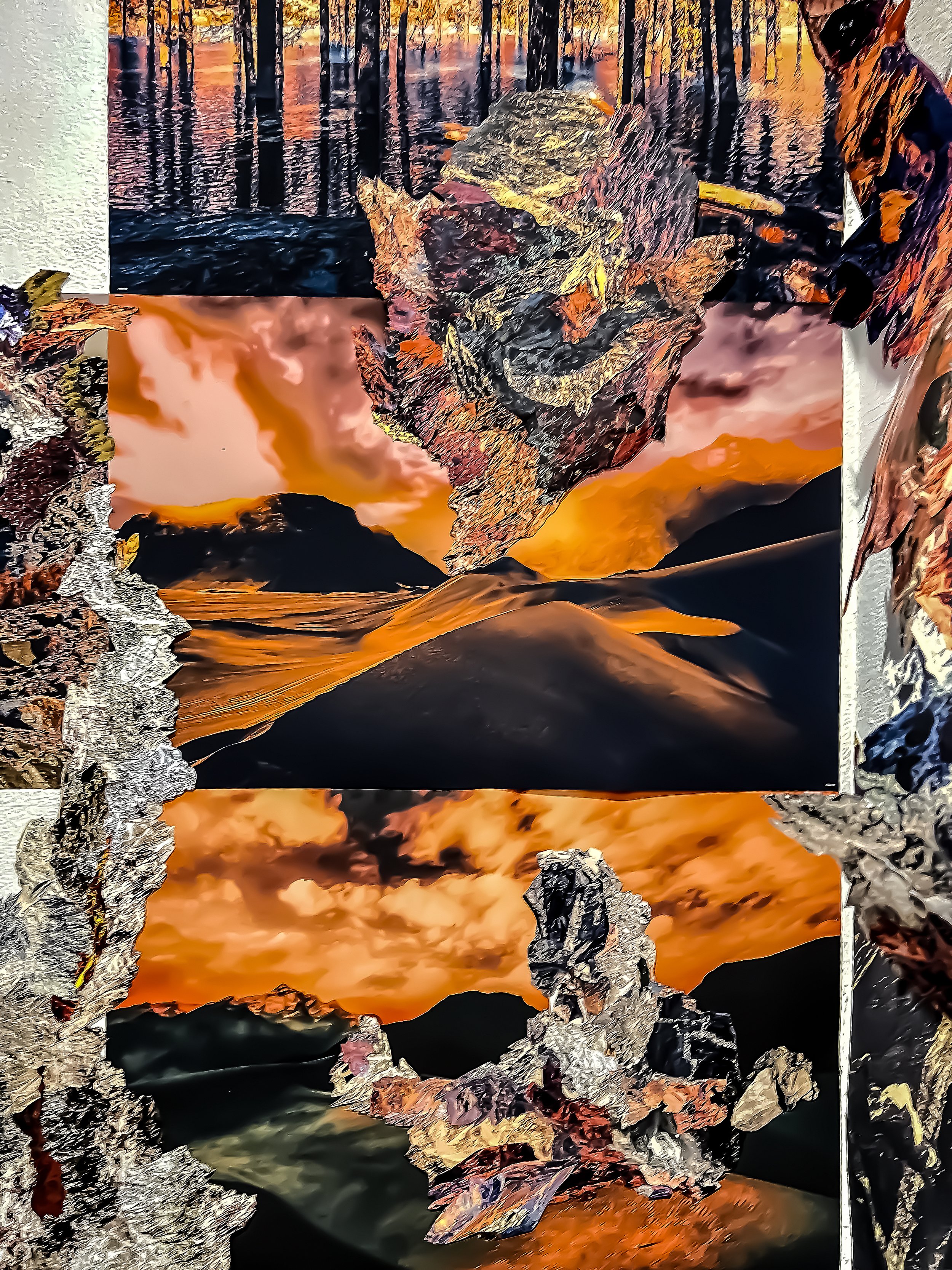

A Conference of the Birds

(Unearthing Stories From The Core series)

(work in progress)

Installation: Mixed-media collage; drawing; salvaged leather

The birds’ ascent suggest migration and narratives of belonging. As an immigrant, belonging for me is not a static identity but a process of continually engaging. A connection with the earth. With the energy and rhythms of creation—our place in the cosmos as part of greater consciousness. An unceasing process of healing from displacement, both internal and physical. A process of reunion of fragmented parts of oneself, and communities.

The birds are abstractions: collaged photos of Gilgit-Baltistan’s majestic and ecologically endangered landscapes. Pakistan is the fifth most at-risk country in the face of climate change. This work emphasizes unexpected alignments via common concerns in Oklahoma and Gilgit-Baltistan, N. Pakistan, and similar at-risk regions in the US. and globally, as climate disaster disproportionately affects native populations.

“The Conference of the Birds” refers to the classic story by twelfth-century Sufi poet Attar. Attar’s tale contains multiple parables within the larger narrative.

I seek to activate a gathering around storytelling. Belonging rooted in sharing histories, embedded in landscapes. Across time and space, cultural, terrestrial. Even celestial, as the birds form a shape based on the Butterfly Nebula’s outstretched wings. In this sense, Alchemy of Disappearance: A Conference of the Birds links with my research of recurring pattern across the natural world—from human body to cosmos—illuminating the universal oneness that underlies existence.

Alchemy of Disappearance

(work forthcoming)

Plaza Blanca or White Palace on Tewa land, with its hoodoos, spires, and eroded rock formations formed from volcanic ash and sedimentary rocks millions of years ago.

In the late 1970s, a group of community-oriented Muslims moved to New Mexico, founding Dar al Islam at Abiquiu, fifty miles northwest of Santa Fe by the Plaza Blanca site. The group commissioned renowned Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy to design a campus, now dedicated to providing a site for “Americans working together for education and social action.” Although the settlement’s progressive goals ultimately did not align with the Saudi funders, leading to a break and dissolution of the project, the campus still stands: an extraordinary fusion of indigenous and middle eastern architecture.

Plaza Blanca, New Mexico

Plaza Blanca, New Mexico

Acts of Disappearance

Reserved Only For Sovereignty

Studio installations & views at the Santa Fe Art Institute (work in progress)

Acts & Alchemy of Disappearance

Mixed-media collage; drawing; salvaged leather; earth detritus from New Mexico, Gilgit-Baltistan, Virginia (NM plants, rocks and soil samples; GB tourmaline, tea bark, herbs, dried apples, and seeds; VA dried walnuts, plants).

Gilgit Baltistan, home to the longest glaciers outside polar regions, is Pakistan’s most ethnically diverse region. And is suffering some of the greatest global damage from climate change, contributing to deteriorating mental health among indigenous and displaced populations. In 2010, a massive landslide buried Attabad village, forming Attabad Lake. Now populated by resorts and the area’s biggest tourist attraction, the displaced people of Attabad were forgotten. While under the administration of Pakistan, the region hasn’t been given statehood status nor representation in Parliament. Exploited for its natural resources, Gilgit-Baltistan is further claimed by India and parts of it by China. (Notably, American media largely refers to the region as “Kashmir.”)

Acts of Disappearance

(Unearthing Stories From The Core series)

(Unearthing Stories From The Core series, in progress)

Mixed-media collage of digitally manipulated photos of landscapes of Gilgit-Baltistan, Northern Pakistan

Acts of Disappearance examines racialized land displacement in marginalized regions of the US & Pakistan. The unexpected alignment reveals both geographic majesty and immense trauma absorbed by contested land and its inhabitants. Acts of Disappearance rests at the intersection of personal narrative, contested land, current ecological devastation, and eco-therapy.

This question of “Disappearance” is multivalent, as is the case with much of my work; I embrace the rich variety of meanings brought by my audience. Most poignantly, the “disappearance” refers to not only the disappearing ecological systems and life-ways supported by these in the face of climate disaster, but also the disappearance of women’s labor, especially within the most economically impoverished regions, globally. Disappearance of green space from urban centers.

Acts of Disappearance implicitly asks: who has access to land resources? The earth offers itself to us for healing and sustenance; how do we honor its legacy and honor those who have historically been caretakers of the land? What reciprocal relationships can we foster with the land? Ultimately what can we learn by sitting with and listening to global hinterland? What do people residing closest to contested land have to share? How do the “we” who are non-Natives form connection with the land outside extractive relationships? Acts of Disappearance seeks to be an offering.

With an understanding that the land carries multiple burdens, my work acknowledges histories of indigenous habitancy, colonial settlement, and current ecological devastation. I explore themes of displacement and renewal, communal healing, and above all: the sublime, restorative potential of nature.

© 2024 Sarah Ahmad. No content on this site may be used without permission. All Rights Reserved.